Please Help Review Or Replace This AI-Generated Placehold…

The frontier era of what would become Colorado, particularly the region encompassing modern Douglas County, represents a complex tapestry of cultural encounters, territorial shifts, and environmental misunderstandings that shaped the American West between 1750 and 1860.

In the mid-18th century, this high plains region existed as a contested borderland between Spanish colonial ambitions and indigenous territorial claims. Spanish influence radiated northward from Santa Fe, established in 1610, reaching toward the Arkansas River valley. Spanish traders and occasional military expeditions ventured into these lands, establishing tentative trade relationships with various indigenous groups, particularly seeking buffalo hides and indigenous captives for the labor markets of New Mexico. The Spanish presence, while never resulting in permanent settlements this far north, introduced metal tools, firearms, and most significantly, horses into the indigenous economy of the region.

The transformation brought by the horse cannot be overstated. By 1750, Plains tribes had fully integrated horses into their cultures, revolutionizing buffalo hunting, warfare, and seasonal migration patterns. The Comanche, in particular, emerged as formidable mounted warriors, controlling vast territories and forcing other tribes to adapt or relocate. The Utes, traditionally mountain dwellers, expanded their range onto the plains seasonally, while the Arapaho and Cheyenne, pushed westward by pressures from tribes further east, began establishing themselves in the Colorado plains by the late 18th century.

The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 fundamentally altered the geopolitical landscape. Suddenly, the United States claimed sovereignty over vast territories it barely understood. The expedition of Zebulon Pike in 1806-1807 represented one of the first American attempts to comprehend this new possession. Pike, traveling through the Arkansas River valley and eventually detained by Spanish authorities near modern-day Alamosa, perpetuated a crucial misconception that would shape American perceptions for decades. His comparison of the plains to African deserts – describing them as sandy wastes incapable of supporting agriculture – established the notion of the “Great American Desert.”

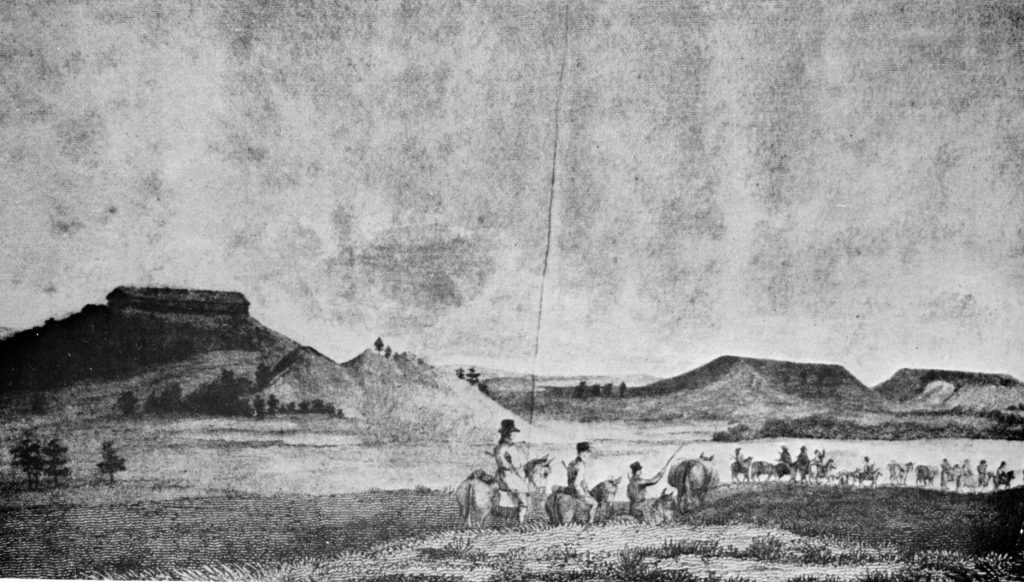

This desert myth was reinforced by Stephen Long’s expedition of 1820, which traveled along the South Platte River through what would become Douglas County. Long’s report explicitly labeled his maps with “Great Desert,” deeming the region “almost wholly unfit for cultivation, and of course uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture for their subsistence.” This perception, while grossly inaccurate regarding the region’s agricultural potential, ironically served as a temporary buffer, discouraging immediate American settlement and allowing indigenous peoples a few more decades of relative autonomy.

This desert myth was reinforced by Stephen Long’s expedition of 1820, which traveled along the South Platte River through what would become Douglas County. Long’s report explicitly labeled his maps with “Great Desert,” deeming the region “almost wholly unfit for cultivation, and of course uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture for their subsistence.” This perception, while grossly inaccurate regarding the region’s agricultural potential, ironically served as a temporary buffer, discouraging immediate American settlement and allowing indigenous peoples a few more decades of relative autonomy.

The period between 1820 and 1840 witnessed increasing tensions as American expansion pressures intensified. Eastern tribes, displaced by American settlement, were forced westward, creating a domino effect of territorial conflicts. The Cherokee, Creek, and other southeastern tribes were removed to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), which in turn pressured Plains tribes northward and westward. The Arapaho and Cheyenne, relatively recent arrivals themselves, found themselves competing with the Utes for hunting grounds and resources in the Colorado region.

Trading posts began appearing along the Arkansas River and South Platte River valleys. Bent’s Fort, established in 1833 on the Arkansas River, became a crucial hub for trade, diplomacy, and cultural exchange. These posts served as meeting grounds where indigenous peoples, Mexican traders, and American mountain men negotiated complex relationships. The fort system created new economic dependencies, as tribes increasingly relied on trade goods while American traders depended on indigenous knowledge and cooperation.

John C. Frémont’s expeditions in the 1840s marked a shift in American intentions. Unlike Pike and Long, who were primarily tasked with exploration and mapping, Frémont’s missions carried an expansionist agenda. His detailed reports and maps, published widely, began to dispel the desert myth and attracted attention to the region’s true potential. Frémont’s glowing descriptions of fertile valleys and abundant game contradicted earlier reports and helped stimulate American interest in the region.

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) brought another dramatic change. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo transferred the southern portion of Colorado to the United States, adding to the territory acquired through the Louisiana Purchase. This created a unified American claim to the entire region but also inherited complex relationships with indigenous peoples who had negotiated various agreements with Spanish and Mexican authorities.

By the 1850s, the frontier dynamics grew increasingly tense. The Utes, under leaders like Chief Ouray, attempted to maintain their traditional territories through diplomacy, while the Cheyenne and Arapaho, led by figures such as Black Kettle and White Antelope, struggled to adapt to diminishing buffalo herds and increasing wagon traffic along the Platte River routes. The Oregon, California, and Mormon trails, while not directly crossing Douglas County, brought thousands of emigrants through nearby regions, depleting resources and introducing diseases that devastated indigenous populations.

The discovery of gold in 1858 near present-day Denver shattered the final barriers to American settlement. What had been a gradual pressure suddenly became a flood. The Pike’s Peak Gold Rush brought tens of thousands of prospectors and settlers into the region virtually overnight. Towns sprang up along the Front Range, and the indigenous peoples found themselves rapidly overwhelmed. The establishment of stage routes and plans for railroads, including what would become the stop at Larkspur, signaled the end of the frontier era.

This century-long period represented not merely a transition between sovereignty claims but a complex interaction of cultures, economies, and environmental understandings. The Spanish colonial system’s influence lingered in trade patterns and cultural exchanges. Indigenous adaptations to horses created new forms of Plains culture that, while often romanticized, represented sophisticated responses to changing conditions. American expeditions, despite their misunderstandings, gradually accumulated knowledge that would enable rapid settlement. The frontier was never truly empty but rather a dynamic space where different peoples negotiated, competed, and sometimes cooperated in ways that would shape the American West’s development.

By 1860, as the railroad age dawned and the Civil War loomed, the frontier period in Colorado was ending. What had been indigenous homeland, Spanish borderland, and American “desert” would soon transform into territories and states, with the accompanying displacement of indigenous peoples and the establishment of American agricultural and mining communities. The frontier era’s legacy would persist in place names, cultural memories, and the ongoing struggles over land and resources that continue to shape the region today.